Sign up for dispatches from our public workshop

Introducing Recovered Factory

Journalists used to unlock data for the public good. In an era of collapse, can that work live outside traditional institutions?

January 19, 2025 · David Eads

Leer en español →

When Argentina’s economy collapsed in the early 2000s, business owners and managers abruptly abandoned their factories and workers, leaving enterprises that still had customers adrift. They were doing useful work, yet were left without the traditional power structures we often reflexively assume are necessary to sustain them.

Facing these conditions of abandonment, workers had to recover the factories themselves. Case in point: the Brukman textile factory faced increasing debts while salaries were shrinking. The workers—mostly women—met with the factory owners to demand better treatment and then occupied the building as a way to force the owners to continue negotiating. But the owners never returned. The workers reopened the factory themselves, rebuilt the client base, and settled the debts.

Brukman still operates today as a worker cooperative, despite raids, court battles, and internal disputes. It is one of the more visible examples of Argentina’s fábricas recuperadas—recovered factories or recovered enterprises—that emerged from the vacuum left behind when institutions failed, and power abandoned these businesses and organizations because they were no longer sufficiently profitable, whatever their social value.

This newsletter takes its name and its inspiration from that idea.

I have spent the past 13 years in traditional journalism organizations, with the previous decade devoted to an eclectic mix of work: in insurgent digital publications; as a founder of the Invisible Institute; doing full-stack software development at places like Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory; and working in community spaces like FreeGeek Chicago.

I’m not the first to say it, but having recently been in the trenches, I can affirm it: establishment journalism is in serious trouble. Outside of a handful of winners in a winner-takes-most ecosystem, these institutions have effectively lost their social role and power—they’ve been abandoned by their leadership and, in turn, have abandoned sustained efforts to reach their audiences where they are.

The rapid growth of the independent creator economy alongside the painful decline of establishment journalism shows how this dynamic has played out in recent years. As Joy Reid recently put it, that kind of media is “cooked.” The war between macroculture and microculture that Ted Gioia predicted would break out in 2024 has weakened traditional institutions even further. The article itself is dying, says Ben Werdmuller.

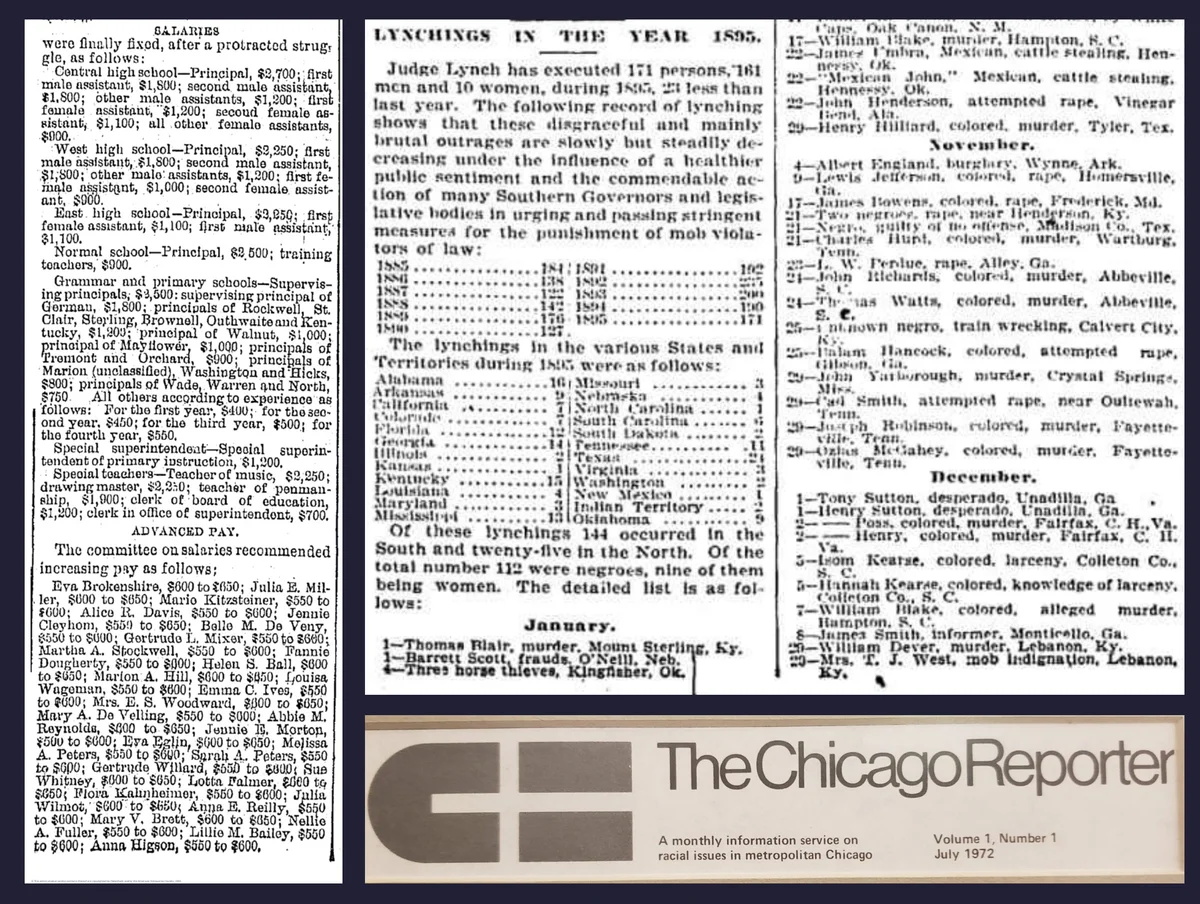

This is especially true for fundamental forms of data journalism, where I have spent my career. Ida B. Wells drew on data collected by The Chicago Tribune for her landmark reporting on lynchings. My friend and colleague Rachel Dissell recently found tables of public salaries in late 19th-century newspapers. When the venerable Chicago Reporter launched in the early 1970s, it called itself an “information service” and published tables full of critical data.

That work has atrophied with the long decline of the field. Cultural authority eroded, economic possibilities shrank, and both vision and basic service deteriorated. It’s nearly impossible to imagine that the Chicago Tribune of today has the resources to track every killing by ICE, for example.

How will this kind of unglamorous public-interest journalism survive outside the organizations that once gave it legitimacy, resources, and visibility? Can it be rebuilt? Can it be financially sustainable? How can it balance playing the algorithmic game with resisting the power of the tech companies themselves?

I’m starting this newsletter not because I have sweeping answers or definitive analysis, but because I’m trying to figure out how to keep my public-service data work alive outside the institutions that supported me over the past decade.

Consider this a kind of public workshop where you can drop by to see what my collaborators and I are making. To start, we’ll be joined by Tory Lysik, a recent Columbia graduate and Axios veteran with whom I had the pleasure of contracting at The Marshall Project. She’s helping build tools and edit these posts.

The newsletter will include field notes—discussions of design choices, how we are defining success, and how things perform in the wild. Our projects will include experiments where we invite your input and support and report on what we learn, like hiring influencers to talk about data journalism. We’ll also publish bench notes that offer deep dives into specific techniques, such as building robust data pipelines, modern web mapping, and multilingual products and publications—including this one, which is available in Spanish and English.

Can this work be sustained outside traditional institutions? You’re part of the experiment. By subscribing to the newsletter or directly supporting the data tools we’re building, you’ll help us find out. We hope to reach journalism funders and others curious about supporting the field. Our perspective is optimistic, but it requires letting go of some long-held assumptions about what journalism should be, and how its value is measured.

And just to add a little frisson of drama and tension to this newsletter—even a skeptic of singular narrative like me knows every story needs some—this is a high-risk, high-reward professional pivot for me. While my permanent residence is in the U.S., I’m spending a lot of time in Colombia these days, a country Trump has recently threatened with regime change. If I don’t go bankrupt or get stuck in the middle of an invasion, this should all go fine.

Stay tuned for an announcement later next week: a Missouri traffic stops explorer we’re excited to share with you.

Sign up for dispatches from our public workshop